Beetlejuice was Tim Burton’s second film. Yet it might be his most recognizable one. It doesn’t have the heart and melancholy of Edward Scissorhands, nor is it as artfully constructed as Ed Wood. But it encompasses everything that makes Burton, well, Burton.

Some thirty-odd years later, at the height of this godforsaken legacy sequel craze, Burton returns to Beetlejuice. I was worried, to say the least. The original means so much to me. It’s an island in time. It ignited my love for Burton, a crush for both Winona Ryder and the hysterical Catherine O’Hara. As a film, it’s pure Burton, and, for a time, all that I was, too.

The first ten or so minutes are a rough landing. Bits work, but there’s a natural ambivalence to everything else. The film spends time picking up pieces of the last three decades and, for a moment, doesn’t go anywhere. Even if a delightful stop-motion sequence does elicit a smile.

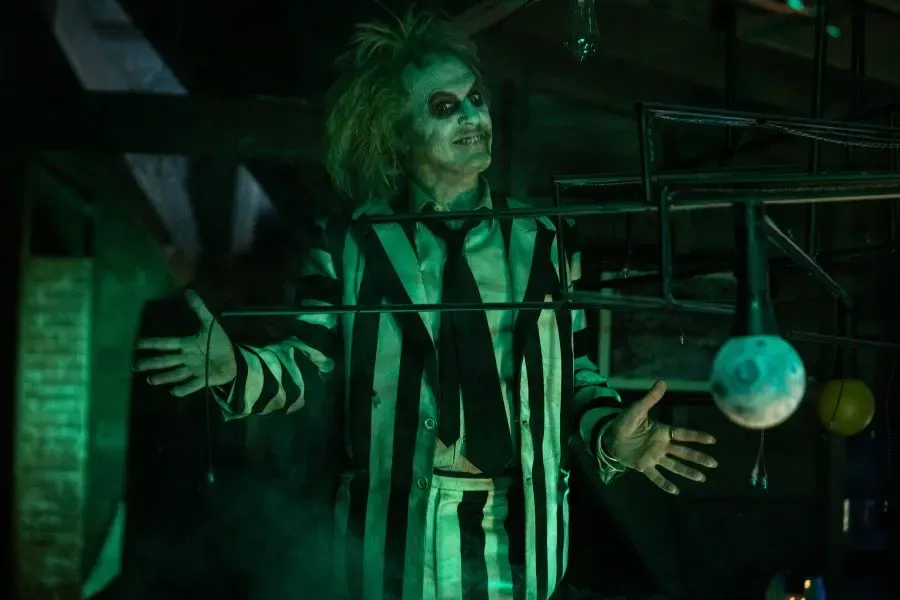

The moment in Beetlejuice Beetlejuice where I knew the film would work comes soon after. Beetlejuice (Michael Keaton, crazy as ever) recounts his past with Delores (Monica Bellucci). Only his voice comes through in as a Spanish mono track, and the picture turns black and white. As if we were watching an old Spanish horror film from the 1950s. No explanation is necessary. It’s just fun.

That same freewheeling energy permeates through the film. Beetlejuice Beetlejuice doesn’t make a lick of sense, yet it doesn’t matter. It piles in ideas, gags, and surprising moments of poignancy to an overwhelming degree. Ask at any point where a character went, and you’ll likely come out confused.

For example, Astrid (Jenna Ortega), Lydia’s daughter, meets and falls for a boy. He has secrets of his own. To uncover them, our characters must travel to the afterlife, which isn’t exactly the afterlife. Instead, there’s a soul train (with literal music to boot), and an entire immigration office to numerous hereafters. Rules upon rules, most of which don’t matter. It makes you appreciate how lean and brutally efficient Beetlejuice was.

Elsewhere, there’s the mystery of what happened to Astrid’s father. Will Lydia marry the sleazy hanger-on she’s living with. Willem Dafoe shows up as a dead actor playing to be an afterlife cop. Beetlejuice still wants to marry Lydia for reasons unknown.

It’s a lot.

A lesser film would stumble under so much plot. Yet here the chaos feels part of the madness. It’s charming instead of overbearing.

That’s largely thanks to the game cast, who relish the opportunity to play in Burton’s playground. The great Catherine O’Hara, returning as Delia, is a particular highlight. She’s an art house nightmare. The very essence of maximalist hysteria for profit. Yet O’Hara makes her endearing, even lovable. It’s a wonderful balancing act of pantomime and sincerity.

The same is true for Ryder and Keaton, playing to their strengths as Lydia and Beetlejuice. Keaton hasn’t aged a day, and his “ghost with the most” still delivers the biggest laughs in the film. My initial fears that his return would feel like a lazy victory lap proved unfounded. If anything, it’s a case of a talented actor mining one of his most famous parts for new material without falling into repeats.

Ryder, in turn, proves once again what a unique talent she is. Lydia is in a poor place when we meet her again. The odd teenager now an odd adult, but without the safety net that youth brings. In a surprising move, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice allows itself a chance to slow down and deal with darker material in its first half, and Ryder is there for it. Her desperate attempts to connect with Astrid and the world give the film much of its heart and soul.

The rest come from the wacky and demented humor, which harken back to Burton’s youth. There’s a gag involving a demonic baby that I never thought I’d see again in his films. It’s anarchic, liberated, and laugh out loud funny.

But for all the wildness and looseness, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is surprisingly sincere. Like Burton’s previous return to his past, Frankenweenie, it never laughs at its legacy. It might smile knowingly, a tad embarrassed at all the things we did in our youth. But it’s never mean, and it doesn’t shy away from who or what it is.

There’s an immense comfort to that. A sense that, like Lydia and Astrid, we can find our place without forsaking who we are. Burton’s talent is speaking for the oddballs and misfits. Us, who belong to the island of lost toys. Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is like seeing old friends, and a warm reminder that sometimes, you can go home again.