I spoke with director Andy Mitton and producer Richard W. King at the Night Visions Film Festival about their latest film, The Harbinger. Our spoiler-free talk covers the anxiety of lockdown, creating a mythology that resonates on a global level, and what terrified us in our past. I had a great time with the duo, and I think their eloquence is reflected in the film, which I reviewed here.

This interview is edited and condensed for clarity.

Both this and The Witch in the Window feel like folk horror and urban legend, and they have very distinct mythology behind them. Are they based on something, or are they just something you came up with?

Andy Mitton: In both cases I made up everything, all the rules with the mythologies, to suit the story. I think I disappointed a few people in the QA when they asked what my relationship with demonology is. Once I figured out what I wanted to explore, I figured I’d devise something to suit this machine.

Explaining the rules is always difficult. It always teeters on over-explaining. Here, you play with the mundane and how grounded the rules feel. You even have the person who knows everything tell the would-be victims off for having a tone!

Mitton: Something I’m attracted to is flipping horror tropes, like the haunted house movie that wants you to stay instead of going, or here a demonologist being stuck at home with her kids. The information comes out, but it’s not helpful to the protagonist. That was the important thing. To have the rules that would help people, but it doesn’t reach them.

I also have a personal connection to that scene because that’s my wife and kids playing the parts! It always delights me when they pop up.

COVID is a major part of this, not just in the story, but in the production, since you filmed during the lockdown. I imagine it must have posed massive challenges.

Richard W. King: From the outset, we had to ask the question, do we make a movie with COVID?

When we started, we had no idea how long the pandemic would last, what shape it would take, and whether anyone would watch this kind of film. Some people recommended not doing it. So we had this entire conversation about whether could make something involving a respiratory disease from a hundred years ago and how that relates to today.

But I don’t think the story suffers from us including COVID. It provides a setting for mythology. I think it also serves as a reference point for future generations.

Mitton: We didn’t want to deal with it on the nose – or on the beak, in this case. The Harbinger is a mythology that could exist in any other story. But here the setting provides us with a dread we all share.

Usually, that fear is something physical, like wars or regional conflicts, but now it’s everywhere. We can’t see it, but it’s there. The big thing is not to be preachy about it. That’s what is great about the horror community, and the genre. I don’t want to see a straight-faced drama about COVID right now. But I think if it has that rollercoaster effect, a kind of cushion built into it, that’s something that works. I think horror audiences are not purely escapists, they want to deal with these things. As long as you check some of the genre boxes, they’re willing to go with it.

Horror audiences are not purely escapists, they want to deal with these things.

Andy Mitton

Like with Soderbergh’s plague movie, Contagion, which found massive success during the lockdown. People want to deal with this in their way.

King: Exactly!

The film has a remarkable moment where the main characters try to connect again, and they’ve forgotten how to be human. I found that terrifying. It was a nightmare of our making. Things we’ve forgotten. It gave me so much anxiety because it was so understandable.

Mitton: The unmasking scene is the heart of the movie. I found the actors really brave for doing that scene. Because it’s not just people masked up in character, it’s also the double-masked people in the crew, and everything involved in the isolation.

If you listen to the film, you hear their hearts beating. That’s not a sound cue, that’s the lavalier mics pushed against their chests. We hear their hearts beat for real. It doesn’t make sense to have it in the audio mix, but we couldn’t take that out. It was too important.

The neighbor is also such a real creation, the person who reminds us that people who hide zombie bites aren’t that far-fetched.

King: I never thought about how it would land with international audiences until we started screening it.

Mitton: It seems like everyone has their own frustration with people who were in the way of common sense and the ability to care for one another, and how frustrating it is. But I thought of her like a grace note in a way. I didn’t want a big arc, but I wanted to address it in a way that wasn’t just me taking my anger out on somebody. We also see her eyes, her own doubt, her own silence, and her hope that she could do things differently. She’s a human being, somewhere deep down in there.

A lot of horror for me is the uncertainty. Like how in darkness we can’t see what’s ahead, so we respond to it in a very subjective way. You either freeze or you have this confident ignorance –

King: Yes, that blind certainty.

The same fanaticism that creates zealotry. I think that’s why her character works so well. It creates the dread of what we can see on top of the fear of what we can’t. It doesn’t feel like a joke.

King: Emily Davis, who plays Mavis, deals with the thing with such sincerity. She offers help, and it’s rejected.

Mitton: It speaks to the talent of Stephanie Roth Haberle, who was there for only one day, that it works. She brought so much to that role. We shot the whole thing in a hockey rink for tax reasons, and she came to set for one day and her reaction was like “what are you doing?” But she’s fantastic, she’s a well-known stage actor, and she brought the catharsis and the humanity to it that we all needed at the time.

The neighbor has her own doubts and hopes that she could have done things differently. Stephanie Roth Haberle brought the catharsis and humanity to the part that we all needed at the time.

Andy Mitton

In The Harbinger, when people leave, when they die, it’s not callous, it’s like the rumble after a thunderclap. It permeates and leaves a mark. Was that intentional in constructing the story?

Mitton: Yes, because at the time I felt, particularly in New York, it was very intense, the national guard was in town, and it was a scary period, lives were lost in droves, the hospitals were choked, and the lost lives weren’t honored. Nobody could come to the hospital to be with their dying loved ones. We wanted to honor that. We wanted that space left behind to feel palpable. It needed to have weight. That existential dread because the stakes felt higher than death because it was a life lost – and then not remembered.

I think it also has left a mark on people, because a lot of the films at the festival here, the genre films, explore the fear of erasure. Of disappearing without anyone noticing.

Mitton: I think there’s important catharsis. Even if people don’t want to go there, when they watch the unmasking scene, you feel them letting it go. Because we haven’t processed it, and it needs to be processed. What better way to do that than in a horror movie?

The Harbinger itself is a terrifying creation. What were some of the decisions regarding how much you show?

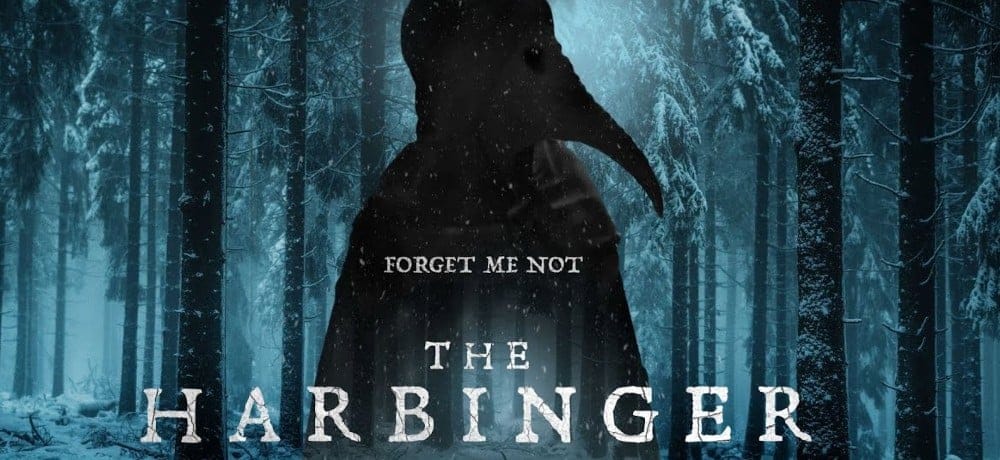

Mitton: I think the strength of this demon is that we get to have a masked bad guy. He’s the designer of dreams. He speaks through other characters in dreams. So that let me keep him in reserve because he’s still everywhere. There’s always value in keeping the terror in reserve. The image of the plague doctor has always scared me. There’s that Freud essay on the uncanny I read years ago and it stuck. It’s all about how you perceive that whatever you’re looking at is wrong, but you can’t put your finger on why.

I like to ask everyone who comes to Night Visions what their most terrifying experience in a film is. It doesn’t have to be a horror movie, but something that just shook you.

Mitton: Zelda in Pet Sematary. That fear goes back to the uncanny. I read in an interview that they cast a teenage boy for that scene, and he was already very skinny, and they dressed him up even further to play her. Watching it at such a young age, I couldn’t tell what was so off about it. It petrified me as a kid.

King: I watched the TV movie of IT way too young. A lot of that was surreal, like the balloon moving a certain way, or Stan in the bathtub. I didn’t understand things like suicide at the time, but I knew that things felt wrong. The climax didn’t land as well.

Mitton: That’s because they ran out of money!

King: But as an eight-year-old, I couldn’t process it. But it was on television, so I watched it, and it never left me.

For me, it’s the opening of Jaws. When Christy, the swimmer, tries to call for help, and she swallows water.

Mitton: Then there’s that rusty buoy in the water. God, everything about that scene is horrifying.

King: We watched that recently in the theaters. The lines that she has, like “help me” and “it hurts”, you’re trying to think is it the acting or is she talking about the rigging? It’s horrifying no matter what.

Mitton: That movie is rated PG.

King: I know! It’s not fair.