Good horror doesn’t just talk about what we fear, it helps us cope with our collective trauma. The horror films of the past that linger in the public consciousness are all about societal anxieties. Jaws is about a shark, but it’s also about the distrust of corrupt officials whose shortsightedness costs lives. Halloween gave voice to the growing fear of home invaders, popularized by the media frenzy around the Manson Family and Jeffrey Dahmer. The monsters are extraordinary, but the terror lives right next door.

In Andy Mitton’s The Harbinger, fear wears a mask, or, more accurately, it might be the mask itself. Shot in the midst of the global pandemic, it’s an eloquent and intensely affecting urban legend about the fear of losing connection and, eventually, yourself. Where other horror films would ramp up the body count to make a point, Mitton’s despair feels almost elegiac in the terror of knowing that the world moves on with uncaring speed.

At its core, The Harbinger is an exorcism story. Set during the quarantine, it follows Monique, who travels to New York, into the heart of the plague, to help a friend suffering from debilitating nightmares. She expects to provide emotional support for someone in a dark place in the midst of remarkable circumstances. What awaits is something else entirely.

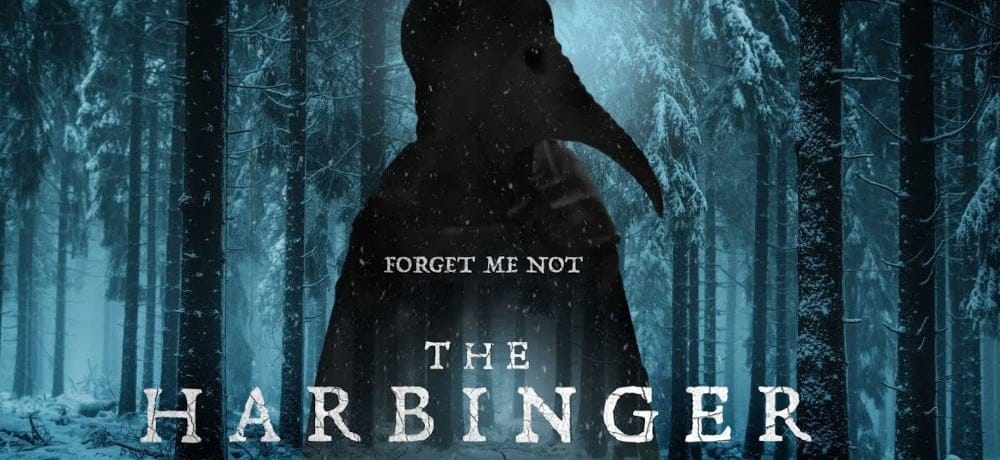

The framework of the film is familiar to anyone who knows the genre. There is a demon, rules, and an inevitability that comes with religion. They’re all different faces of the same fear. Knowing its name is like knowing the number of the bus that hit you. The titular creature resembles a plague doctor, complete with a long, birdlike beak, and black eyes not-unlike the void. As far as metaphors go, it’s not subtle, but it doesn’t need to be. We don’t wake up demanding more nuance from our nightmares. They’re scary because they articulate that which we cannot. Mitton’s film does the same.

What separates The Harbinger from others, and elevates it beyond plaguesploitation, is how it understands inherent truths about our fears. A neighbor lashes out at anyone who dares to follow quarantine procedures. We get the sense that she’s already alone. The isolation should make her feel more connected to others. The masks, the protocols, and the increased separation only highlight how alone she is even during a time when others reach out to make a connection. So she rejects help, she screams, because it’s the only way someone will notice she was even there.

Later, as two friends reconnect, there’s a ritual to reaffirm their humanity. The masks fall, they gesture awkwardly, and the very act of a hug feels like a skill they must relearn. In the distance, we hear someone cough, and it’s like the air rushes out of the room.

On my first viewing, I wasn’t sure if the big picture worked all the way through. The second time around, I didn’t care. I let myself wash away with these moments of tenderness that tiptoe around the precipice of fear. It’s thanks to them that the nightmare feels more real. We’re still not out of the woods, but there’s comfort in knowing there are others wandering here, too.