David Marmor came to Night Visions with his feature film debut, 1BR, and I got a chance to talk with him about the difficulties of first features, the mundane terror of apartment complexes, and why Los Angeles keeps attracting cults. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

1BR is your first feature film. Can you tell me about how it went from concept to finished product?

DM: It depends on where you want to start; it’s kind of a long story. The script I had written a long time ago was one of my first efforts, and it was on the shelf for a long time. Much later, I got representation as a writer, and my managers asked if there were any other scripts I wanted to show, and all I had was this old script sitting on the shelf, and grudgingly I gave it to them to read.

I had naturally progressed as a writer by then, but they responded to it. They agreed it needed a rewrite, but they felt that if I made another pass on this, they’d be interested in producing it. So I spent a few months writing it, changing it from the ground up, and Alok (Mishra) and Shane (Vorster) stepped in, and from there, it was about six months until we began shooting.

The pre-production almost killed me because the script wanted to be made for about three times the budget we actually had, and it was a struggle to make it happen. We had fifteen days to shoot, so it kind of came together miraculously.

You had another actress cast in the lead too?

DM: Yes, Nicole (Brydon Bloom) was my top creative choice for the role, and the producers I think liked her as well, but we were such a small movie. This other actress was so well-known that we decided that we could make our money back on name recognition if she were in it, even if I screwed up the film.

We cast her, and I flew out to Toronto to practice with her, and then about four days before we were supposed to film, she dropped out without any explanation. I don’t think she wanted to give up her vacation, as we were shooting over the Christmas break.

That must feel like the whole thing would fall apart at that point.

DM: Especially since we also lost out male lead, as we had cast her boyfriend in the role, and then in an unrelated matter, we lost the actress of Mrs. Stanhope since her husband fell ill – which was horrible, obviously – so we were out three of four actors right before filming.

So we offered the part to Nicole, and we couldn’t think business at that point, we just wanted someone we liked, and luckily she said she’d love to do it. She’s New York-based, and she hopped on the plane the next day, and we had one afternoon to rehearse before we began filming.

It’s grueling to make a movie like this already. Still, pre-production had been so difficult that actually getting on set felt like a relief. Before that, it felt like everything would fall apart. It felt like such a privilege even to make the movie that it gave me extra energy to make the film.

Los Angeles is an inherently scary place; it’s everywhere; it’s a centerless sprawl. Was the intention always to have the city as a character in a horror story?

DM: Yes, it’s based on my experience of moving to LA in my early twenties. I didn’t know anybody, and you just feel like you’re drowning in humanity – as you said, there’s no center to it. It’s forty miles from the ocean, and it’s very easy to feel lost there, especially in these apartment complexes that feel very anonymous. Nobody knows anybody, you might wave to one another, but you don’t know anybody. That feeling was very powerful when I first got there; that was the seed of the idea.

It’s a small set in a big place. I read that you found the courtyard for real, but everything else was built.

DM: Yeah, the courtyard is a real apartment complex. Very populated, too, so we were constantly holding for the people to go in and out of their apartments. A few of them wanted to be in the film, so they show up as extras in the apartment. But the apartments are sets, and it’s actually one set that’s re-dressed for the four different apartments. I’ve had many people who’ve watched the film who haven’t noticed this.

It helps that the actors are interesting to watch, especially the leader of the cult —

DM: That’s Taylor Nichols; he’s fantastic.

He has a kind of Roy Schneider kind of air about him: a very calming and soothing presence.

DM: The credit for that goes to Alok, who knew Taylor, and Taylor was a lead in Metropolitan, the Whit Stillman movie, and Alok is a massive fan of that movie. He once met Taylor at a party and went over like, ‘I’m a huge fan, I’ve got a poster in my apartment and everything,’ and they hit it off. When we got to casting this, Alok suggested that his friend would be ideal for this part – and I looked at his stuff, and he was right. There’s something about Jerry, this benevolent energy, he believes that he’s absolutely the good guy, and you need someone who can convey that.

There’s something terrifying about someone who wants to comfort you when they’re doing something awful at the same time.

DM: Absolutely! (Laughs)

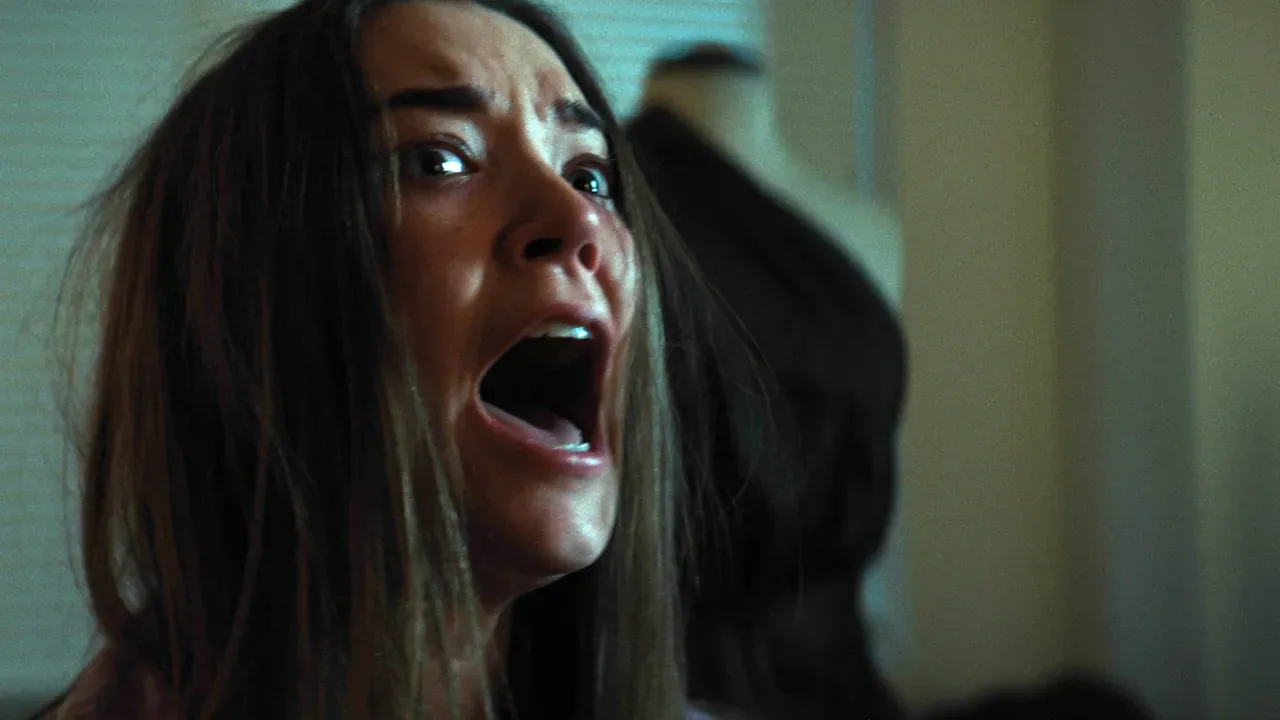

There’s also an enduring trope, iconic even, of the wide-eyed girl at the center of this horror and violence. Why do you think that image continues to be a staple of the genre?

DM: I mean, I think that for me, when I originally wrote this, Sara is very much me, or how I felt when I arrived in LA, and I combined that with the backstory of a female friend of mine. I had to make a conscious choice about which kind of story I was making. And it might be my sexism or societal sexism at large, but it felt like there might be more peril if it was a woman involved.

We don’t go there in the movie, but there’s always the subtext that there might be sexual coercion involved; there’s that threat still. In the society we live in now, I felt like it wouldn’t function the same way if it were a male character. It felt that you wanted to have the character feel like they were in the worst danger possible.

When I first read the synopsis, I was initially skeptical because the genre is so overflowing with torture porn.

DM: That was one of the significant changes that I made when I wrote the script. I cut it down to make it as small as possible while still making us understand what she goes through because it’s much more interesting, anticipating what comes next, rather than the violence.

I read you worked at a games company before you got into film. Games are all about player interaction and the reactions you get from them; did that experience help craft a horror film?

DM: Not consciously. I spent three years after college at this game company, but I was basically a coder. I had done graphics stuff in college, 3D graphics, but when I helped start this company, I was responsible for creating the graphics engine when I helped start this company.

The irony is that I was never a big gamer. I’m sure that I was absorbing something about how people interact with things by being there and seeing the process, but it was never a conscious part of what I was doing. I gained from those years more in terms of a similar kind of creativity as programming; it’s sort of like engineering, problem-solving – you start with inspiration, and then you try and make it work. So it’s putting that puzzle together. Those skills helped me with writing and directing; there’s a technical component to it that this experience is useful.

First drafts, especially, are just a mess.

DM: You just spit them all out on the page. This was something I had been through in short films. You’re always writing the movie, even after you’ve locked the edit, all the way until you’re doing ADR; the whole time, you’re making story decisions. We were making these choices days before locking the DCP (the Digital Cinema Package), just days before the first screening.

When I made my first short, I realized how much of the actual shooting is just collecting material, and the actual film is made in the edit.

DM: There’s a great metaphor I heard from Ridley Scott years ago at a seminar. He said that a director is a chef, shooting the film is going to the market to buy the ingredients, and making the film is the cooking.

I read somewhere that you might also be considering a sequel.

DM: It’s on the table, but we’ll have to see how this does. There are certainly more stories to tell, and I’d like to see where Sara goes next. But it’s not something we intend to do.

We’re working on a new film, a totally different genre, and I’m working on the second draft of the script and hoping to get it made next year.

When I went to LA for the first time, and the first time someone pitched Scientology to me, I was baffled. It doesn’t happen here, so someone actively explaining why this cult would be the answer for everything, blew my mind. What in California attracts cults?

DM: I think it’s specifically an LA thing, which is unscientific. I think it has to do with the kind of people that LA attracts. It’s a city, but it’s a giant metropolis full of transplants. It’s people like you and me who’ve come there pursuing something. Dreamers and seekers all crave something; they want a connection, a spiritual awakening. That makes people vulnerable to organizations like this.

On the flip side, it makes people want to create something like that. When I started reading about these groups, many of them started with good intentions. Synanon, the group this is based on most, began as a drug rehab group. They wanted to help people that nobody wanted to help. That’s because there is a need and desire for it.

Michael Mann talked about that when he made HEAT and COLLATERAL, it’s a sparsely populated place looking for a connection. Synanon was something that I had heard about years ago that wanted to fix people whether they wanted to be fixed.

DM: The really scary moment was when they decided that nobody is ever cured of their addiction. That flips the whole thing around – ‘you have to come live with us’ – and suddenly, the entire thing has changed.

That seems to be a recurring theme with all cults; they all start as families and accepting, and then it’s suddenly not. When folks in L.A. were pitching Scientology to me, thinking I had money –

DM: You actually listened to the recruitment?

I figured: “Why not?” I was only visiting, and I had no money, so the joke was on them –

DM: I bet you saw them lose interest in you quickly.

Oh, immediately. Suddenly all the pretty girls inviting me in were gone, and there were just the guys telling me where the door was.

DM: That’s probably the best result in this case!

And that’s the thing with these cults; now we know precisely how they operate, with GOING CLEAR and other documentaries now in the mainstream.

DM: Yeah, ten years ago, the info was out there, but you had to look for it. It wasn’t as open as now.

But it’s not like these cults ever advertise themselves as cults. They’re always branded differently, and I think that’s something you captured in 1BR: the overwhelming kindness that buries the malice.

DM: Thank you. It was definitely what I was going for, a Polanski-ish, not super-heated, ‘this is what it could feel like.’ None of these groups believe they’re a cult; they’re a family, they’re an organization. Never a cult.

In regards to real-life horror, it reminds me of JESUS CAMP.

DM: You know someone else mentioned this as well about 1BR.

They share the same elements, how it just starts a bit weird but seemingly harmless, and then just descends into this horrific madness. You’re, of course, removed from the whole thing, but it just scares me. 1BR has a similar structure of welcoming the mundane and then breaking down pretty quickly. It even extends to how you shot the location – the entire place is built so that there’s no getting out of it once you’re in.

DM: That was one of the lucky features of the location and why we picked it. It had exactly what I needed, which was how cheery it was, the pool, the trellis, everything, but when you look at it, it actually looks like a prison, with walkways and gates on multiple levels.

There’s also the element that all these houses are copy-pasted monstrosities, and it’s something I saw while living in Houston; these places are all built by the same company but have beautiful names.

DM: Yeah, and they’re all the same; Paradise, Cove, etc. Houston is very much like LA, it’s just a sprawl, and they just keep adding loops to it.

LA does lend itself to a variety of genres; why did you choose horror?

DM: It was just the natural feeling, a horrible feeling, the malice of people staring at you across the breezeway. It wasn’t calculated; looking back on it, it was a lucky decision. Horror is good for a first feature. You can get away with it without having a big budget or stars, you can make an impact by telling a story you want, and people will see it.

If I had written an action movie, I couldn’t make it without money. It was lucky that this happened to be the story I wanted to tell. It just was organic that the idea itself was a horror film.

What’s the scariest film you’ve seen? Not particularly horror, but scariest.

DM: That’s tough. If you’d asked me as a kid, I’d have said RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, because that gave me nightmares. It opens with the guy getting spikes through him, and then, in the end, you have people with faces melting off.

Spielberg traumatized me with JAWS when I saw it at like six or seven years old.

DM: I saw that much later. I can’t even imagine seeing that at that age.

There are horror films that I adore, more than the answer I’m going to give, but the scariest one I’ve seen is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the original one. It’s a movie I love, but not something I want to watch a lot because it’s just so upsetting.

There’s something about the film’s tone that feels authentic, so grubby, that you feel like you might be watching a documentary. The wrongness of that movie is so palpable. And when she gets away, the look on her face, I remember thinking that – she’s not OK.

She’s never getting out of there.

DM: Exactly, she’s still in there, somewhere, and that to me is one of the scariest moments in cinema.