This is a deftly directed and well-acted film that is reprehensible to the core.

It is a rewrite of history catering to right-wing politics by targeting the two favorite punching bags of the MAGA crowd; the government and the media. Arguably the first example of weaponized pop culture for this decade.

The facts are worth repeating, especially since they’re absent from the film. In 1996 a pipe bomb exploded at Centennial Olympic Park, killing one and injuring over a hundred others. Moments before the explosion, a security guard named Richard Jewell discovered a suspicious bag containing the bomb and alerted the authorities. His actions saved countless lives.

Once the dust cleared, the FBI named Jewell a suspect. The story leaked to a reporter at the Atlanta Justice-Constitution, leading to a trial of public opinion. Though cleared of suspicion, it took years for Jewell to be exonerated and acknowledged for his actions.

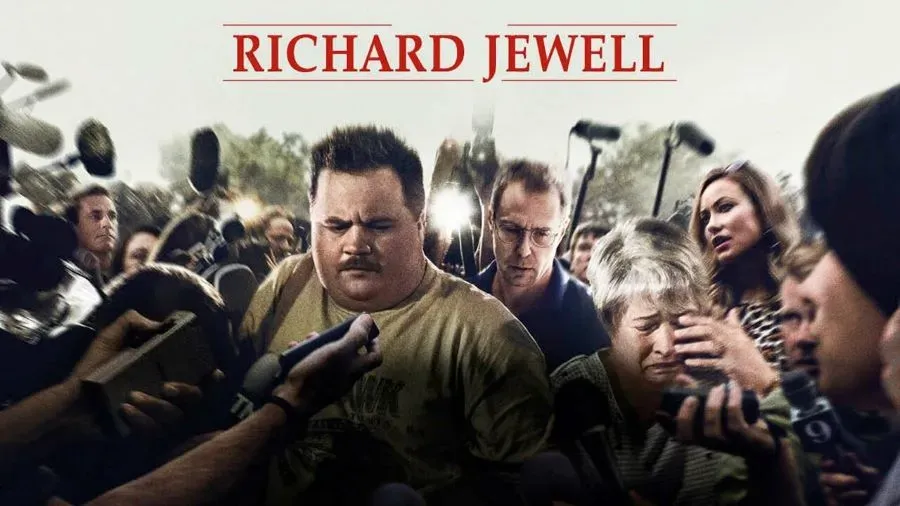

Is his story a tragedy of overreach and hysteria? Absolutely. But that isn’t what interests director Clint Eastwood and screenwriter Billy Ray. To them, Jewell is a means to an end, a political straw man of the highest order. Played as a Holy Fool by Paul Walter Hauser, Richard is an overweight sad sack living with his mom (Kathy Bates), who plays video games and is desperate for a father figure. Eastwood and Ray play up Jewell’s shortcomings so that the entire thing feels like a backhanded compliment. Surely he couldn’t have done any of this, just look at him.

I’m not sure if this is the kind of defense anyone deserves.

In this highly fictionalized re-telling of the bombing and aftermath, Eastwood’s Jewell is a naive doofus, whose only crime is wanting to protect others. The film depicts his struggle to maintain his innocence not as a story about mass hysteria brought on by a scared, uneducated public; but as a horror story of liberal media run amok. In the process, Eastwood and Ray besmirch the name and legacy of a real person no longer around to defend themselves.

That person is Kathy Scruggs, the journalist who first reported on the FBI’s suspicions regarding Jewell. Once it came out that the investigation was meritless, Jewell sued both Scruggs and her employer, AJC. During the trial, Scruggs was ordered to reveal her source within the FBI or face jail time. Protecting her sources, Scruggs said no. Later, those closest to her reported that the aftermath broke her, and the fallout caused her health to deteriorate. In 2001, five years after the bombing, Scruggs died alone of a prescription drug overdose. Four years later, the lawsuit was ruled in favor of Scruggs, declaring her reporting had been accurate.

In Eastwood’s film, Kathy Scruggs (played by Olivia Wilde) is an alcoholic opportunist who trades sex for story leads. A wreck so incompetent that her coworker finishes her stories. Every other character related to the investigation is a fictional composite with no allusions to their real identities. They are also all men, led by the fictional detective Shaw (Jon Hamm). Though their methods are overreaches of power, there’s a silent acknowledgment that no matter how horrible their actions are, the men are only guilty of working for the government. Wilde does what she does because she’s a woman. With no sexual favors to trade, her part is shut out for good. For Eastwood, nothing is more terrifying and necessary to vilify than a journalist with a vagina.

When making a film about the past, simplification is unavoidable. A two-hour film has limited space, and every biopic is reductive. That is acceptable. But when making a statement about the importance of facts and how their callous handling can potentially ruin lives, there is an obligation to adhere to the truth. Every omission will be under scrutiny, as each change comes with an agenda. Some changes are easily understandable: Placing Shaw at the park during the explosion allows a personal connection to the event. Combining a team of lawyers into one (Sam Rockwell) is just clean writing. These are not, and never have been, the issue.

But artistic license only carries so far. A montage of multiple newspaper headlines superimposed over Olivia Wilde’s face, with the implication they were all written by her, is not simplifying things. It’s flat-out lying. After multiple repetitions of this, a man finally explains to her how wrong she is. After that, Wilde has only one line of dialog in the film: “He’s innocent,” she says, teary-eyed. If only, the film insinuates, had she just listened to men first before forming an opinion.

So how can it be a well-directed and acted film? Mainly due to two things: Eastwood knows where to put the camera and how to craft a scene. After half a century in the business, it would be tragic if he didn’t. The cast, led by an always reliable Sam Rockwell, plays their parts as well as the insipid script allows them. The bombing sequence is tense and superbly orchestrated.

It is important to acknowledge the film's merits because it makes the following carry more weight: This is a polished piece of propaganda masquerading as a prestige picture, designed like a dog whistle for a crowd with their ears perked up for one.

A brief scene halfway through the film sums it up nicely: Richard is under scrutiny, so his lawyer advises him to list any extremist organizations he or his friends may have come in contact with. Baffled, Richard asks for examples. His lawyer rattles off names, eventually coming up with the NRA. “The NRA is an extremist organization?” Richard asks with utmost sincerity.

In 2020, after a decade of bloodshed by lone white terrorists belonging to the same cult, this kind of willful ignorance is positively astounding.

Discussion