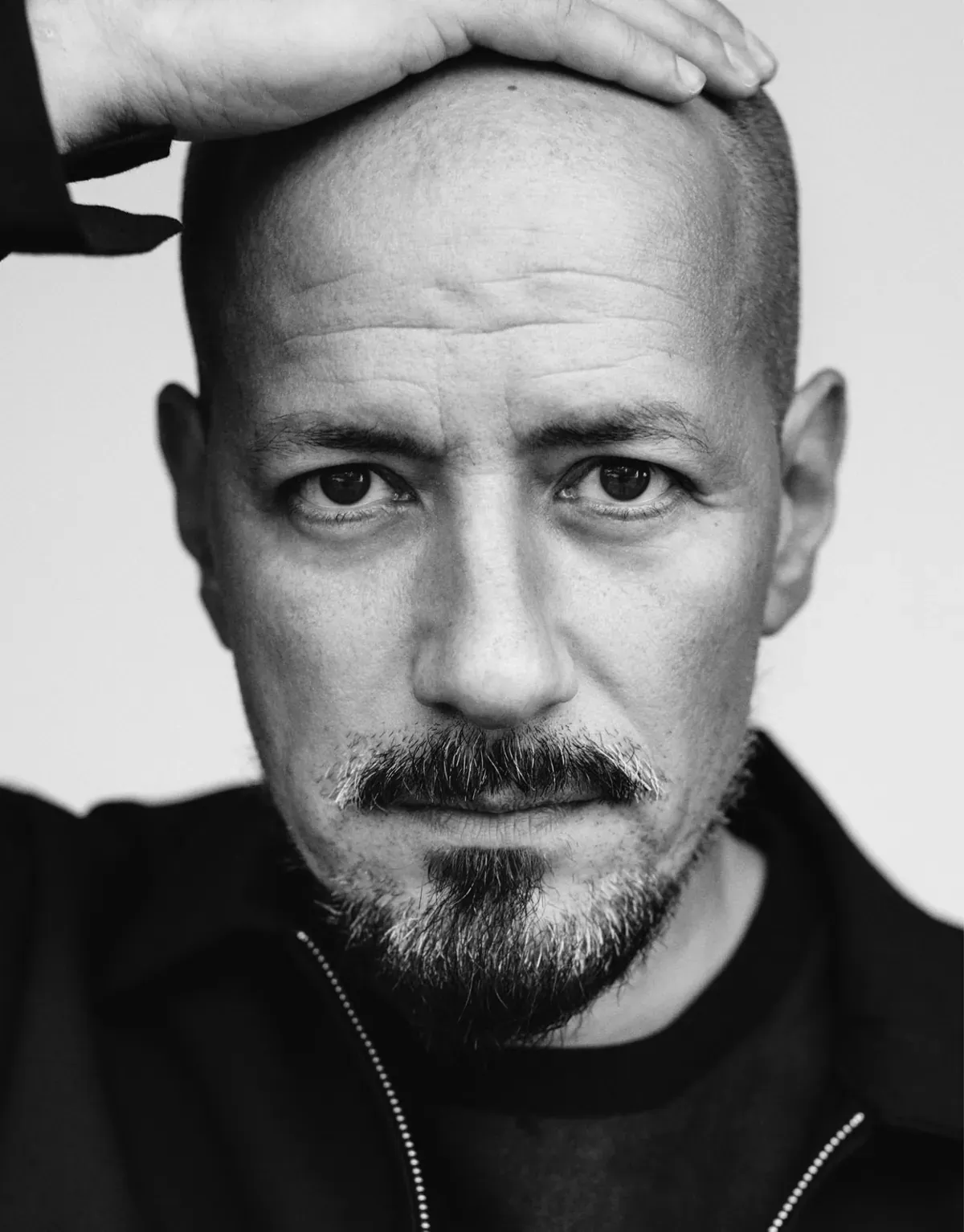

It's the last weekend of the Toronto International Film Festival, and the marathon is starting to take its toll. But I couldn't leave without meeting with Tarik Saleh and Fares Fares, two Swedish filmmakers who are behind some of the most interesting Nordic cinema in the decades they've been active in the field.

Their latest, Eagles of the Republic, is an unnerving thriller about an Egyptian actor caught up in a government propaganda film, where his part is to play a fantasy version of the new president, against his every instinct and principle. As the compromises pile up, his deal with the devil starts to eat away at him, leaving nothing but ruin and devastation in its wake.

Our conversation is edited and condensed for clarity.

Joonatan Itkonen: Eagles of the Republic is a film that deals with people orchestrating and creating a false image of a country that never existed. To me, that is a fascinating topic, because as filmmakers, you're creating memories that are not real. When you began work on the film, did you have a specific idea about how to approach this contradiction?

Tarik Saleh: It's a very interesting and good question, because I'm reconstructing my own memory of Egypt [making this film], because I have not been able to return there since 2015.

I have a very strong emotional tie to Egypt, and it's a complicated one because I grew up in Sweden, but, when you're a child of an immigrant, you are constantly told stories about the country where your parents come from. So, my father would talk so much about Egypt, I would create this very strong image in my head of what it would be like to live there. It's a very nostalgic picture.

So, the first time I went to Egypt, I was 10 years old. It was an absolute shock. I was confronted with something completely different than what he had said. It was as if he had been lying, basically. Of course, because it was his memory, he was in absolute shock too.

It was the first time he returned to Egypt in years because of political reasons. This was right after [Anwar] Sadat had been killed, and the country looked like a war zone. It was so poor, in my mind, coming there from Sweden.

So, from that point, I started to try to and meld together what I saw and what I experienced. I went to university, I started a magazine in Egypt. I was constantly trying to create my own version of Egypt.

Now, the paradox is that it’s been 10 years since we were thrown out, when we were shooting The Nile Hilton Incident. We shot Eagles of the Republic in Istanbul, not in Cairo, so we had to create a reconstruction of the country as well.

So, not only is the film within the film a lie, but the film itself, in a way, is a representation of our relationship to Egyptian cinema and TV.

JI: How did that appear in the depiction of the hero, George Fahmy, and the industry?

TS: We have been joking together, ever since we got to know each other, about Egyptian films and movie stars and how they act, or rather overact, because they are larger than life.

One of the biggest living stars, his name is Adel Emam, and he's so big it's difficult to even translate it into a Western actor. But he does not really do characters. He's acting as himself in different movies.

Writing the script, I thought about the first time I came to New York when I was 15. I felt like I was coming home, and I had never been there. But because I've grown up with the skyline, with the streets, with the yellow cabs, it creates memories that are not yours. That's how strong of a propaganda tool it is.

On top of that, the majority in Egypt can't read and write. So, the relationship to film and television is absolutely massive. This is how people experience reality.

So, they will go and watch these films and get sort of a sense of collective idea of what Egypt is. Another detail is that in Egyptian film and television, you're not allowed to swear. They have not gone through sort of the naturalism we had with Elia Kazan in the West.

That means that when they swear in our film, the language is very, very rough. So when Egyptians see the film, they say Egyptians don't speak like this. But what they refer to is the way Egyptians speak in film and television.

I ask: “You don't say that in the street?”

“Yes, in the street, but not on film.”

So, the naturalism of our film becomes a sort of heightened reality for Egyptians when they watch it. It's absurd.

Fares Fares: I remember that we discussed about it for one scene especially. I have a dialect coach. My Arabic has kind of lost a lot of its power, let's say, when I moved to Sweden. I'm from Lebanon, so I had speak like an Egyptian, which is like Swedish and Norwegian or even Swedish and Danish, more or less.

We were discussing one scene where I want to say something to my girlfriend that was probably obscene. My dialect coach goes: "You can't say that. We don't say that!"

What do you mean you don't say that? Like, a man and a woman in bed wouldn't talk to each other like that?

"No."

And there was Egyptian extra next to us, who also said: "Yeah, no, they don't say that."

Then after a while, we realized they don't say it on screen.

I had to tell them that I don't care they don't say it on film, do they say it like with each other in reality? Then this is how we're going to do it.

So even the language, like Tarik says, is completely controversial in our film. Which is liberating if you're Egyptian. I could hear that yesterday, watching the screening, when it was Egyptians laughing at something they don't normally hear on film. They were laughing like at a swear word or something.

JI: There's also the frankness to the film, like the scene where you go and get Viagra. You're just trying to escape the reality, and people keep recognizing you. I thought it was great not just because of the absurdity, but because it allows for George to be vulnerable, to admit they have an issue that is perceived as a lack of masculinity.

TS: It's interesting. That scene actually happened to me, the Viagra scene, in Egypt.

My wife was pregnant, and I was going to buy something that she needed. She was six months pregnant, and I was alone in the pharmacy, and the guy is like, do you need anything?

I was like, no, I don't need anything.

Then he started to present different versions of Viagra for me. I told him I really don't need it; and then other customers started to come in and there's no way they think that he's doing that on his own. They think I asked for this!

I had small sort of snippets of being half famous in Sweden in the 90s, when I was a TV host. I remember specifically that you always get recognized when you absolutely don't want to, when you are sort of in a vulnerable position. That's when someone is like: "Oh, it's you!"

For Fares, it’s different. Fares is among the five most recognized people in Sweden. We had a conversation about the script where he said something that really got to me about what it means to always be recognized. You said maybe once a week, one person in Sweden doesn’t know who I am, and that's a strange feeling.

It's the opposite for everyone else, the idea that everyone knows who you are.

I knew, writing the script, this is not something Fares will have to imagine for the part.

FF: George, the character, he kind of enjoys it; I've never really enjoyed that.

Except I understand, even when you're going to a hospital, you get a different kind of treatment, or going out to a nightclub and you skip the line. All that is nice.

But you kind of live in a bubble in a way. That scene in the pharmacy, it’s George Fahmy in a bubble. Like you want to live your life, but you're aware that, okay, someone's going to recognize you. There was a challenge with this character to make that part likable.

Because before that he lies to everyone he loves, and this is the scene where you start liking him, because, like you said, it makes him human in a way. So, it is one of the very important scenes, even though it's very funny.

TS: I think you picked up on a thing that I'm very interested in regarding masculinity.

Because there is a paradox, and especially when you've worked in Hollywood a little bit, because of course, masculinity is something that has been an obsession with basically in all entertainment.

You try to present this image of the masculine man, and the problem is that it goes against being an actor and an artist, this shallow idea of masculinity, because a good actor needs to have sensitivity, vulnerability, and be connected to his emotions.

My father-in-law, he's a fireman. I can tell you, he could never be an actor because when I ask him, how is it to pull out dead children out of a burning building? He will answer: they're easier to carry.

And he's not joking when he says that, because they're lighter to carry than a grown up.

I will ask: but how does that affect you emotionally?

"Well, you feel for the parents when they cry and scream, but you have a job to do there. You need to go in there. You have to try to save the people that are there."

He's just absolutely turned off emotionally, and that, of course, is the icon of manhood: don't feel, push it down.

I'm very interested in that, and I think it's one of the hot button topics of our time. I think it's a part of why I love George: he's very emotional.

He lies to everyone, but he is true in his emotions, which is something that most men have a real issue with, including myself. Because even though I'm quite feminine in my appearance, I am a classic toxic male in the sense that my job as a director requires you to turn off a lot of emotions.

You have to just say, it doesn't matter, we must move on, it doesn't matter how you feel right now. Which, a lot of the time, when I come back to be with my children and with my family, it takes me a long while to get in touch with my emotions and be vulnerable again. I love George because he allows a different kind of masculinity.

Not to be pretentious about it, but I think that when I started working as a director, I had a real problem with actors. They scared me because they were so emotional. I felt like it's too much, there's too many emotions.

But Fares and I are very close. We are very similar in many ways. I think that Fares has helped me understand that you can be emotional and still be a man.

But the point is that this character was very interesting to investigate, because as much as we can throw stones at him, at the end of the film, we're all George Fahmy. We all bend to authority, and once we're bent too much, we'll break.

It's not necessarily ugly. It is human. He's trying to, ultimately, protect the people he loves. Of course, this power is a double-edged sword. When George is perceived to have the power of these “friends”, he helps his neighbour. Then he tries to help his colleague, but that turns deadly. It’s as if he has a contagious disease. Everything George touches dies.

JI: There's also a little bit of like self-sabotage. He knows it's a bad idea to go and have an affair, but he’s unable to help himself because there's that thrill of the chase, at least how I read it.

TS: He's a gambler, and he likes high stakes.

JI: I wanted to ask about that, because as a performance, it's so nuanced in how it starts off as a person who, like you say, wants to help and please others, but a part of that pleasing is a bargain of sorts. George knows that if he pleases them, they like him more. He’s a person who is willing to first make compromises for their soul, which then becomes a question of how much can he sell of himself for that little bit of an endorphin rush.

Did you have a moment looking at the script where you knew George crossed the line? Like this is where he stops being in charge of the thing?

FF: As an actor, I've never done that, where I put different colours to different emotions and have a technical way of approaching it. For me, it's all organic and gut feelings.

Now, am I lucky or is it just that I have really good gut feeling? I don't know. But we talk about the script so much that I do have control of the full arc of the character. I know exactly when to come in and do what I need to.

Where that comes from, I can't say, it's impossible to know. I guess it's organically created.

TS: It's the script.

FF: It's the script.

[Both laugh]

FF: Also to be able to surprise yourself. Because, on the day when you're there and doing the scene, if something else happens, but that you haven't prepared before, you have to be open to go with that flow as well.

TS: I love the process in that way. One of the things Fares does that is almost like black magic to me is, for example, in the scene when he is confronted with Dr. Masoor, who is the real director behind the director. George steps out and he realizes the director is taking notes from this guy from the house of the president, and he steps up to him.

In each take Fares gives, when I sit in the editing room, it's incredible because you are absolutely convinced as he steps up to him that Fares is going to beat this guy.

You're going to use your power and just entirely destroy him, and then, this guy just puts you down.

The fall is so high, and the vulnerability in that, if I had cast it wrong, it would be a mirror actor who has sort of decided with colours what he's going to do and how he's going to play that moment.

Fares does not play that moment. It's as if in every take he thinks he's going to win. And when he loses, it's so painful. Even for me, because I don't want to see him fall that far.

I think that that's the part of the film where we start to say: Yes, this is us.